In the world of education, the results of PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) always attract a great deal of interest. Not only because they measure students' performance in mathematics, reading, and science, but also because they offer valuable information about their family and socioeconomic background. In this sense, the support a student receives at home can make a big difference.

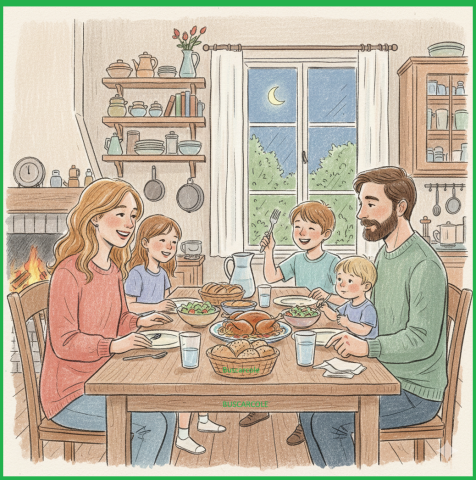

Family support: more than just dinner together

According to Funcas analysis of PISA, generic “support” is not enough: certain specific gestures are most closely associated with better academic results. For example:

- Regular family meals (at least once or twice a week) are linked to a significant improvement in maths.

- Asking children about their day at school also has a positive impact.

- AEncouraging teenagers to get good grades works, although to a lesser extent.

- On the other hand, constantly talking about whether they should continue studying (for example, to go to high school or vocational training) does not always translate into better performance: it could be a strategy used by families to motivate underperforming students rather than spontaneous support.

These gestures convey attention, interest, and, in many cases, a sense of emotional security: values that can also encourage dedication to study.

In addition, Funcas points out that not everyone receives the same level of support: there are significant inequalities based on gender, socioeconomic background, or migrant origin. These imbalances can contribute to the persistence or even widening of educational gaps.

What do the recent PISA data tell us?

Although there is no data from PISA 2025 yet, the most recent reports (such as those from PISA 2022 and the results published in 2023–2024) provide relevant information:

- According to the INEE (Ministry of Education), the international PISA 2022 reports are now available, covering not only mathematics, reading, and science, but also creative thinking and financial literacy.

- In financial literacy, 25% of Spanish 15-year-old students are at the highest levels (levels 4 and 5), according to La Moncloa.

- However, there are also warnings: nearly 42% of Spanish students are unable to interpret simple invoices or pay slips, a figure very similar to the OECD average, according to El País.

- In terms of creative thinking (a relatively new dimension in PISA), Spain stands out in terms of equity: the difference between socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged students is lower than the OECD average, according to RTVE.

- At the regional level, the Community of Madrid and Castile and León are leaders in creative thinking within Spain, according to El País.

- Finally, one of the most notable challenges: Spain has few “excellent” students in PISA (highest performance levels), especially in mathematics, which is concerning because these levels reflect more complex skills such as solving new problems, according to El País.

- A problem in the classroom has also been identified: for example, 33% of students say they are distracted by their cell phones during math classes, according to Telecinco.

Connecting family support and new educational challenges

The combination of family support and recent PISA data suggests some interesting reflections:

- Beyond traditional academic performance: today, it is not only how much students know that matters, but also how they manage their finances or how they think creatively. Family support can also influence these dimensions.

- Family-focused education policies: promoting initiatives that encourage family dinners or spaces for dialogue could be a powerful pedagogical tool. It is not just a matter of “doing homework,” but of building an emotional climate that favors learning.

- Social equity: given that family support varies according to socioeconomic status, working to reduce these inequalities can help level educational opportunities. Tutoring or family support programs could be part of the solution.

- Preventing distractions in class: with data such as high cell phone use in class, it is urgent to think about strategies to improve the learning environment. But the home also has a role to play: if there is a family culture more oriented toward study and dialogue, interest in learning may be reinforced.

Conclusion

Family support is not just a nice extra: it can have real and measurable impacts on student performance, especially when it translates into concrete gestures of attention and communication. Combining this analysis with recent PISA data reveals a promising path for improving educational outcomes: not only through school reforms, but also by strengthening family involvement.

If we want students not only to get good grades but also to develop deep skills—financial, creative, critical thinking—we need to work together at home and at school.